Autumn at Abhayagiri

Late October found the smoke that thickened Abhayagiri’s sky in August gone for clear autumn air, the three deer that usually roam the monastery’s garden replaced by hundreds of families visiting from the city. With the three-months annual Rains Retreat finished, the community’s wider family drew together on October 28th to celebrate the Kaṭhina ceremony. One monk explained:

“In traditional times, the three months of the monsoon season was a time for the early monastic communities to settle in one place. Anyone who has lived with a group of people knows that communal harmony doesn’t come easily. Diverse people spending time together in close quarters for a long period in harmony is a difficult and rare thing to find. The Kaṭhina ceremony is a celebration of that attempt at communal harmony, and is a chance for the laity and the sangha to cement their relationship — the laity providing gifts and material support and the sangha providing inspiration and a refuge.”

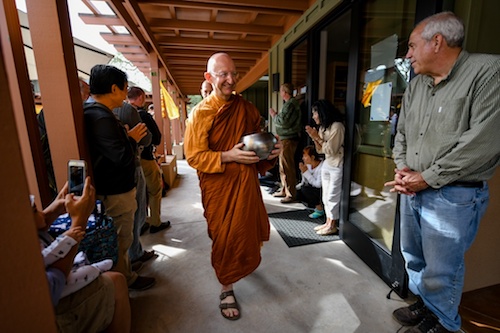

The Kaṭhina represented a chance for all those connected with the monastery to gather. Luang Por Amaro, who founded Abhayagiri over twenty years ago with Luang Por Pasanno, travelled from his current post as abbot of Amaravati Monastery in England to join in the festivities. Other senior monks, such as Ajahn Jayanto, abbot of New Hampshire’s Temple Forest Monastery and Ajahn Sudanto, abbot of Washington’s Pacific Hermitage, also flew in to be part of the celebration. While over twenty monastics came for the event, some of Abhayagiri’s supporters still felt anxiety at the prospect of a Kaṭhina with Luang Por Pasanno gone on retreat overseas. Corina, a regular guest, commented:

“I was concerned when he left. Although I’ve been here for a few years and seen how the work duties have been spread out and how capable everyone is, I just wanted to make sure everyone else knew as well and would continue to come. So, I was reassured that it was well-attended and smoothly run. The Kaṭhina’s a chance to see old friends — it’s a joy. Additionally, I enjoyed seeing the visiting Ajahns and listening to the talks. Here’s where I can speak about Ajahn Amaro. It was really nice to be able to talk with him after the Kaṭhina — just have a Q & A on the deck — and my partner, who hasn’t seen him since 2011 or so, was inspired to become more serious about practice and come up here more.”

Apart from sharing a meal, formally offering gifts to the Sangha, and listening to teachings, the several hundred people who attended October 28th’s event witnessed the traditional sewing of the Kaṭhina cloth. The monks worked together to quickly cut and sew offered cloth into a robe for an honored monk by the end of the day as a symbol of communal harmony. The ceremony finished late in the evening with Ajahn Sek Varapañño, a monk of over twenty-years from Thailand, quietly accepting the robe the community made him as a sign of their gratitude. Dyed with heartwood from the madrone blanketing Abhayagiri’s hills, the robe matched almost perfectly the other hand-sewn robe Ajahn Sek wears dyed with wood from Thailand’s jackfruit trees.

Following October’s Kaṭhina, Luang Por Amaro remained for two weeks, catching up with old students, giving teachings, and becoming familiar with the various changes to Abhayagiri. He spoke about the recently finished reception hall and cloister, and the absence of the old house that held the kitchen and office from when he founded the monastery in 1996 until 2017. Most often, however, he ended his talks praising the new generation of monastics that have stepped forward to lead the community in his and Luang Por Pasanno’s absence. “The strong, new shoots of green,” he commented, “have begun to grow up through the old.”

While Ajahn Karuṇadhammo smiled wryly at being referred to as a “new shoot of green”, he and Ajahn Ñāṇiko have stepped into their roles as co-abbots with energy. Apart from overseeing the completion of the Reception Hall, cloister, and the accompanying ceremonies, they have worked to accommodate growing interest in ordination. Never before have so many young men come to the monastery with hopes of taking on robes. November featured, not just the full ordination of Tan Rakkhito, but the going-forth of one of the monastery’s four white-robed postulants into the intermediate stage of novice. Anagārika Jordan, now Sāmaṇera Jotimanto, spoke about coming to train at Abhayagiri:

“When I first encountered Buddhism, I was in college and had a lot of spiritual inclinations, but I kept them to myself because they were against cultural norms. One example is drinking or drug use. In college I was in a milieu that supported these things, but when I encountered Buddhism, I saw an institution and doctrine which supported these feelings I’d been having. That gave me confidence in myself because I was no longer just an oddball trying to feel my way in the darkness. I just think about the life I would probably be living if I weren’t here. It would be fine I’m sure, but I wouldn’t be a real example of human potential if I just lived the life I was living. I feel like here, we’re a profound example of goodness in the world that doesn’t exist in very many places. I think it’s good to have people who represent counter-cultural values who can, at the very least, show us that it’s okay to go against the stream of society.”

With ceremonies completed and Luang Por Amaro gone, the monastery draws inward in anticipation of the three-month winter retreat. From the beginning of January until April, members of the community put aside their usual duties and re-orient towards formal meditation practice. One monk comments:

Kaṭhina’s the end of our busy season. With all the ceremonies and visiting teachers we’ve had, this year has been truly wonderful, but I think the community’s really looking forward to winter retreat. It’s an important counter-balance to the ceremonies. When the weather starts turning cool and wet, it’s an encouragement for us to go to look inwards for warmth and spaciousness.

Monks use the quiet of retreat to experiment with various austerities as a means of deepening their meditation. Even in the winter months, some choose to continue living outside in the wilderness instead of one of the monastery’s small huts. One monk, who’s lived in the forest for over a year, speaks to the practice of dwelling at the foot of a tree:

“One of the major benefits is that it helps with the traditional elements contemplation. When you’re cooped up in a heated building, it’s difficult to experience the body in its natural state being subject to the varieties of weather. When one spends time outdoors, one has to pay attention to such natural conditions as wind and rain. Living simply doesn’t automatically mean being miserable, but what it does mean is that to not be miserable — to not be wet and cold — you need to pay attention to those things; to know how to set up an appropriate shelter, and enter without getting your things soaked. For someone like myself who spent most of his former life living indoors behind computers screens, it opens up new aspects of your mind and practice. There’s also a sense of wholesome pride in being able to live comfortably in a harsh environment, and those skills transfer directly into formal practice in terms of calming and controlling the mind.”

Such practices exemplify a monastic tradition that embeds itself in the natural environment. Just as the monastery’s acorn woodpeckers begin to quiet in anticipation of the winter months, the year’s activity settles into the stillness of winter retreat. As a year of departures and new arrivals ends, and the community finds itself again moving back towards a center of silence and simplicity.